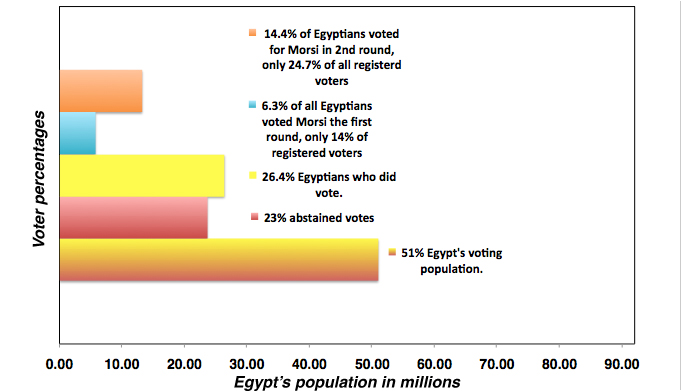

The draft constitution continues on its course, however, and will go to the polls on Saturday December 15, 2012. Morsi has said many times that he was elected by majority, 51% in fact, and it is that majority he is banking on right now.

The numbers in perspective

In Egypt, 51% is not the majority.

Lets go back to May of this year, when we had our first presidential elections, and everyone was pumped about a democratic Egypt. Based on a population of 92 million with a voter turnout of 28.7%, his initial 5.8 million votes was support from little more than 6% of the entire Egyptian population. Even among voters he only had 24.7% of votes. In the run-off his 13,230,131 total vote count was the voice of only 14% of the population, but it’s the 51% of voters that Morsi is banking on.

What it really means is that 86% of the people of Egypt, me being one of them, did not give their voice to our current president. Morsi came in to lead a country whose social, economic and political systems were in turmoil, and a people that didn’t really want or trust him or his band of brothers. It was a recipe for disaster.

President Mohamed Morsi only got 24% of eligible votes in the first round. 76% of the voter population either refused to vote for him, or were not encouraged enough to go to the polls and give their voice to anyone.

Could have Morsi done it differently?

Nasser Amin, General Director of The Arab Center for the Independence of the Judiciary and Legal Profession and an anti-Mubarak activist since 1988, gave me the answer to that question on February 16, 2012. Amin focused his work on understanding transitional justice, preparing for the eventual removal of former President Hosni Mubarak in order to help ease Egypt into a democracy.

“Above anything else, transitional justice in any revolutionary country serves to calm the people and give them pride in the success of their fight and ease the pain of losing loved ones,” he said

Amin’s transitional justice plan was simple. Create an independent, government-funded and fully transparent truth and fact finding commission to work on fact-finding pertaining to cases that address the issues on which the revolution was ignited (corruption, police brutality, government embezzlement etc.). Use special courts to try crimes committed during and leading up to the revolution. Appease the families of the martyrs through concessions and by building a memorial for them. Create a comission And stop using force against protestors.

These steps intended to do one thing: clear out the past, and usher in a new phase in Egyptian history. They were simple , and did not require broad sweeping powers to the executive office. Their success would do more than promote a single political power, it would build trust between a government and its people.

The Supreme Council of Armed Forces had ignored Amin’s suggestions, and dealt with the situation as if they were still in Mubarak’s Egypt. The result was a divided country among enflamed parties. He had hope that the next president would be someone who was a true believer in human rights and democracy.

Our president has disappointed us. He’s dealt with political opposition in the same way as his predecessor, consolidated power to the executive office and broken most of his campaign promises (BBC: Egypt: President Morsi’s 100 days in power). More important, the Egyptian people are no closer to understanding the way our public institutions work, or what our specific rights and responsibilities are as citizens. Instead, he’s given us a constitution that uses the same ambiguity as its suspended version, and infringes on more rights. (BBC: Comparison of Egypt’s suspended and draft constitutions).

Nasser Amin put his final faith in the power of the streets:

“The revolutionary force is the base and it will be what changes Egypt. This is the first time in Egypt’s history, from the days fo the Pharaohs the decision is from the eyes of the street below, and not the eagle eye view of the high offices. What is new is that the decisions come from the square and the streets and that egypt has a new force to make decisions that is very different from its traditional means.

Revolutions are not done by 88 million, they are done by half a million. No one should worry, ever.”

Except maybe Morsi.

Nasser Amin on Ibrahim Eissa’s show Al-Tahrir titled: “What happens after a revolution?”